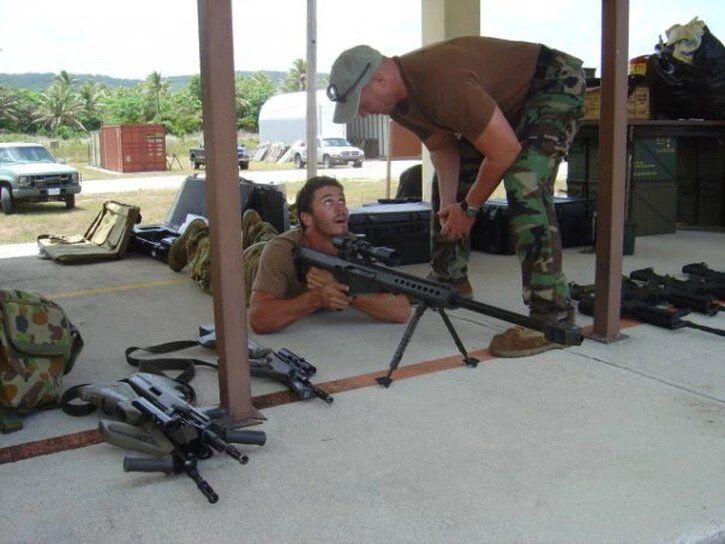

First, in all services, military leadership qualities are formed in a progressive and sequential series of carefully planned training, educational, and experiential events—far more time-consuming and expensive than similar training in industry or government. Secondly, military leaders tend to hold high levels of responsibility and authority at low levels of our organizations.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, military leadership is based on a concept of duty, service, and self-sacrifice; we take an oath to that effect. We view our obligations to followers as a moral responsibility, defining leadership as placing follower needs before those of the leader, and we teach this value priority to junior leaders. Our leadership extends to caring for the families of our soldiers, sailors, airmen, or marines, especially when service members are deployed. When serving in crisis conditions where leadership influences the physical well being or survival of both the leader and the led—in extremis contexts—transactional sources of motivation (e.g. pay, rewards, or threat of punishment) become insufficient. Why should a person be motivated by rewards when he might not live to enjoy them? Why would a person fear administrative punishment when compliance might lead to injury or death?

Soldiers in such circumstances must be led in ways that inspire, rather than require, trust and confidence.

When followers have trust and confidence in a charismatic leader, they are transformed into willing, rather than merely compliant, agents. In the lingo of leadership theorists, such influence is termed informational leadership, and it is the dominant style of military leaders.

Contrast the military leader value set reflecting service to the one that currently exists in some US businesses. Are we likely to see business leaders placing the well-being of their shareholders and employees above their own? Yesterday, February 4, 2009, in a swift response to public outrage, the Obama administration imposed a cap of $500,000 in pay for top executives at companies that receive large amounts of bailout money from the US Government. From a military perspective, a half million dollars is a generous sum, more than double the compensation of a four star leader in charge of a theater of war.

But the quantity of compensation isn’t as relevant as the message to followers that, when times were tough, the leader put his or her personal well being ahead of theirs. Such perceptions of a military leader in combat would render that leader mistrusted and ineffective in the eyes of soldiers forever. Why should business leaders expect anything else on the part of people desperate about the loss of their equity or employment or lifestyles? The current economic environment, partly caused by a crisis of self-service leadership, has created belt-tightening reminiscent of a world war, with budgets slashed, travel funding restricted, training programs cut, personnel layoffs, and other draconian, cash-saving measures in place. CEOs have to start leading like generals—even if that means living a lifestyle in common with their troops.

The best leadership—whether in peacetime or war—is borne as a conscientious obligation to serve. In many business environs it is difficult to inculcate a value set that makes leaders servants to their followers. In contrast, leaders who have operated in the crucibles common to military and other dangerous public service occupations tend to hold such values. Tie selflessness with the adaptive capacity, innovation, and flexibility demanded by dangerous contexts, and one can see the value of military leadership as a model for leaders in the private sector.

In your own development as a leader, have you found value in putting other people first? Did it seem out of place in competitive, results-oriented businesses? Did it powerfully influence people, or did it merely suggest weakness? And have you had role models in business who you see as effective because of their servant leader orientation?